Building a World-Class Civil Service for Twenty-First Century India — S.K. Das

I bought this book on Amazon, and it’s probably the best piece of literature that I’ve read on the Indian Administrative Service. S.K. Das retired from the IAS as Secretary to the Government of India, and he has been in touch with my research adviser. Hopefully he’ll end up working with us; we shall see. Anyway, his writing provides many insights into India’s civil service that are rooted in solid literature about organizational theory and organizational change. I tend to think along his lines, which is actually quite reassuring. At least it shows that I’m not thinking up crazy ideas on my own.

I bought this book on Amazon, and it’s probably the best piece of literature that I’ve read on the Indian Administrative Service. S.K. Das retired from the IAS as Secretary to the Government of India, and he has been in touch with my research adviser. Hopefully he’ll end up working with us; we shall see. Anyway, his writing provides many insights into India’s civil service that are rooted in solid literature about organizational theory and organizational change. I tend to think along his lines, which is actually quite reassuring. At least it shows that I’m not thinking up crazy ideas on my own.

Here is the first paragraph of Das’ first chapter. It provides some background on the IAS that we have today, which is actually built upon the remnants of India’s colonial past. This demonstrates why the civil service needs so much reform.

The civil service that we have today was founded by the British during the colonial days. Its structure and practices derived from that of Whitehall in the mid-nineteenth century, developed on the basis of a career service with tenure until retirement age, subject to satisfactory conduct. The British had set it up to exercise control over a large but potentially subversive group of native employees in the government. They had put in place a complex array of rules, regulations, and processes to maintain control over the decision-making of native employees. The organizational set-up was hierarchical to ensure a clear-cut chain of command based on a rigorous system of reporting. Since the native subordinates could not be trusted to take decisions, it was necessary to force the decision-making process upwards; this resulted in excessive centralization. The result, on the whole, was the creation of a rigid, hierarchical, centralized, process-driven bureaucracy.

Today’s IAS has many characteristics that were leftover from colonial times. It’s centralized, hierarchical, leader-dependent, and process-driven instead of results-driven. The big issue, though, is not just to diagnose the problems but also to find solutions through, for example, case studies of officers who were able to make a difference in the current system.

A Little Case Study: Access to the National Archives

Mid-way through my last research meeting with my adviser at the Raintree Cafe, we were joined by my friend and fellow Fulbrighter. After listening to us discuss public administration for some time, she lamented about the research obstacles that she’s currently facing. Basically, she wants a pass to the National Archives, but the Director won’t grant it to her. Instead, he makes her return repeatedly to the archives and requests a different type of documentation with each visit. His last request was a letter from the US Consulate, which would require a trip to Chennai and $50.

Now why doesn’t the Director just let this US researcher have a pass? It doesn’t require any extra effort on his part. It’s not that he’s comfortable in his position and doesn’t want to lift a finger beyond signing off on papers. I mean, all he would have to do is sign off on papers! Here are some thoughts:

First, although the Director is in a position of authority in name, he doesn’t really have the authority to allow anyone into the archives. Basically, he’s risk-averse. He does not know what his superiors would think, and he doesn’t want to get into trouble for letting her in.

Second, this situation demonstrates that public organizations in India are process-oriented, not outcome-oriented. The extreme documentation and ridiculous, made-up requirements are simultaneously 1) ways to appear legitimate, 2) ways for high-up, central leaders to exercise control at the ground level and 3) safeguards for bureaucrats closer to the ground level, who don’t want to take responsibility for potentially bad decisions. Now, if someone was just like, Hey, let’s let the foreign girl in because she can utilize the National Archives to promote this country (a conclusion of outcome-orientation, which needs to be possessed by organizational leaders at al levels), then we wouldn’t have this problem. Obviously, these “official” processes are failing because of their high inefficiencies and lack of connection with positive or negative outcomes.

Funny enough, despite the ad-hoc “official” process, there is perhaps a more effective, better-trusted, non-standardized, unofficial process for getting access to the archives. My adviser more or less advised my friend’s adviser to call up the Director and vouch for her. This is more effective than any letter, since a human voice/face builds much more confident. Since she hasn’t tried yet, I’m not sure whether or not it will be effective. If it is, though, then the official process is quite the sham and a waste of resources.

An Long Overdue Research Recap

A few days ago, I finally met with my research adviser to talk about research, that fuzzy activity that the national government is paying me to do. We had an interesting discussion that basically recapped the few interviews I had conducted before I left the country. From the discussion, I could instantly see where my adviser and I disagree. I am aiming to get to the root of why officers are afraid to take initiative as leaders in their positions, and I am utterly convinced that it’s a structural problem, not an individual problem. My adviser, on the other hand, believes that it’s more personality-based — or, at least, based on an individual’s ability to communicate and an individual’s understanding of his/her organization’s goals. [And these points are but subpoints, since getting a superior on your side and knowing organizational goals contribute to lessening risk.] In the end, I want to believe that we can enact reforms within entire Indian Administrative Service that promote autonomous decision-making and leadership by providing a safe space for leaders to be leaders.

Although my adviser may think otherwise, I will stick with my guns until I find something better: a huge reason for why bureaucrats do not take decisions is because they are afraid. They are risk-averse, and the entire system is set up for risk aversion. At the lower level of bureaucracy, officers actually have limited authority and need to get clearance from the center (the Indian civil service is hierarchical and rigid, and it is based on an outdated system that was initially supposed to be a way for the British to maintain control over the locals; more on this later). Additionally, there is very little reward for decisions that end up with good results and severe punishment for decisions that end up with bad results. Officers have many watchdogs, and political bosses can actually do things to officers that they’re unhappy with (e.g. unearth tainted pasts, file lawsuits, etc.).

However, I do see that at a certain level of seniority, officers also get quite comfortable and lazy with not doing anything. At this point, perhaps the issue is less about fear and more about laziness/lack of accountability regarding concrete outcomes. Given that officers rotate posts every two to three years and that promotions are based on years in the service instead of effectiveness, there is just not that much incentive for officers to put their hearts into their jobs. Additionally, top-level IAS officers both create and implement policy, which not only takes up time but creates another excuse for not taking action (that is, if officers don’t create a policy, then there’s nothing to implement and no measuring stick for failure or success to take action). As I mentioned earlier, the officers think much more about themselves and their comfort instead of their organization’s effectiveness and the people their organizations are supposed to serve.

During my discussion with my adviser, one idea that I didn’t take issue with was the fact that the IAS needs a sustainable leadership model. Basically, organizations are less known for their organizations than they are known for their leaders. When the leaders leave organizations as headless chickens, the organizations fail to function. Middle management is filled with yes-men who will do whatever the next leader wants, even if it means repealing a policy implemented by the previous leader. There is little space for middle management to take up authority, as decisions need to be approved at the top.

Another idea that came up was this issue of external management. My adviser said something along the lines of, “In India, it’s all about external management. If you’re a master of external management, then you can do anything.” That basically means that if an officer can get politicians on his/her side, then he/she can do anything he/she desires. This honestly makes me a bit wary. First, if officers had real authority, then they’d have so much space to act and to innovate. Since they don’t have real authority, they don’t act or innovate. Second, this doesn’t seem to hold officers accountable. If all they need is the go-ahead from the top, who’s to make sure that they both create and implement policies that deliver services to the public? And what about input from the public?

Anyway, more thoughts to come. I’m reading a fantastic book right now about the Indian civil service and will update with more information from it shortly.

What People Really Want to Know (aka How to Google this Blog)

Forgive the recent lack of updates — I’ve been away, back in the States. By being in the US, I managed to miss Diwali in India. And by being in India, I managed to miss Thanksgiving in the States.

But here I am again, back in Bangalore, and hopefully getting back into my research. I personally feel like it is coming to a gradual slowdown, since not much has happened to pursue more interviews or generate more findings since I’ve been away. Additionally, the rate at which actions are taken — professional or otherwise — is pretty slow, and it takes much time to re-rev up our research engines. Alas! But I suppose that one of the purposes of being on a Fulbright — that of cultural exchange and promoting mutual understanding — is being fulfilled by simply going through the process of attempting research here. The actual research findings? Perhaps they’re secondary.

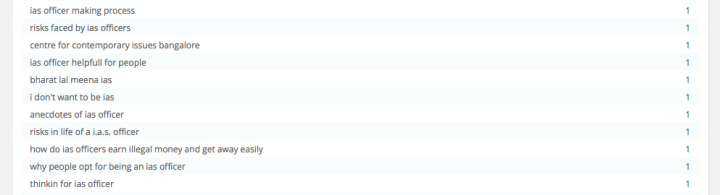

Anyway, since I have few legitimate updates, I thought I’d post about something that I find interesting. Every once in awhile I check this blog’s visit statistics. In particular, I’m interested in what people are Googling to find this blog.

The results are pretty interesting. While my name does top the Google search term list (thanks, Mom!), a lot of people are Googling information about the Indian Administrative Service. And a lot of people seem to have the same questions/thoughts/concerns that I have. Or maybe that’s just what I know because that’s how Google works — whatever, just play along with me. Regardless, here are some sample search terms that have led here (regarding any typos: I claim [sic]):

- why ias officer is powerful

- making of an ias officer

- can a ias officer really make any change

- how ias officers make money from private sector

- can ias officers take decisions themselves

- what are those factors that affect iass?

- risk faced by ias officers

- risks in life of a i.a.s. officer

- ias officerhelpfull for other people

- can ias officers take decisions themselves

- are ias officers corrupt

- can a ias officer really make any change

So it turns out that at least a few people out there are thinking about the same questions and issues that I’m thinking about. Although this is a difficult subject to study (because it’s somewhat sensitive, because it’s rather large and requires a more pointed question on my end, because I can’t go about it on my own without going through my adviser), it’s well worth the effort. Hopefully I’ll have some answers to these questions, at least before the upcoming Fulbright conference.

What Affects an IAS Officer’s Decision-Making Risk?

I had to curtail yesterday’s post about “corrupt” officers because it was getting too long, and I was running late to a meeting (okay, I wasn’t really that late, since I did manage to pick out 20 pieces of specialty chocolates for my meeting folks at my favorite new café/bakery). Today, I want to flesh out a few more ideas about what affects an IAS officers’ decision-making risk.

In my previous post, I wrote that an IAS officer makes decisions based on perceived risk and not on greediness or being evil, as some people like to believe. Like any regular people, officers are going to look out for the safety and well being of themselves and their families first. Certain decisions – even if mandated by law – will put an officer and his/her family at risk because there are powerful stakeholders who dislike the decision. These stakeholders, unfortunately, can determine where the officer works and can ruin the officer’s name. Despite the power that has been granted to them as part of India’s executive branch, IAS officers these days aren’t very free to exercise their power.

With the understanding of risk as foundational to decision-making, I’m starting to see how other “corrupt” aspects of public administration fit. Bribes, for example, are less about greed and more about insurance (the thinking goes, Well, even if I get in trouble for making this decision, at least I get a house out of it). Additionally, the lack of decision-making by officers is just a consequence of there being too much risk involved. Doing nothing is safer/less risky than doing something.

For IAS officers to make the “good” decisions that I honestly believe most want to make but feel like they can’t because of reasons x, y, and zed, then we need to understand the factors that affect risk. And perhaps these factors can be examined through case studies of “effective” IAS officers, which is what I came here to study anyway. Sure, those righteous IAS might exist. But I’d like to believe that the majority of those who’ve made a positive effect on Bangalore/Karnataka did so without a martyr-like mindset. Plus, if they’re still around the IAS and didn’t get pushed out of the system for being too good (something that ex-officers tell me can happen), then, well, some of the conditions must be right.

So here is the beginning of my list of “factors that affect an IAS officer’s decision-making via implications on personal risk” (or something like that; working list name):

1. Amount of support/protection of a boss who is more powerful than those forces that can otherwise influence you.

One of my research adviser’s go-to examples of an “effective” IAS officer is a particular ex-Commissioner of the Bangalore Development Authority. My adviser tells me about how this guy kicked powerful encroachers off of BDA-owned lands and auctioned off these lands to earn more money for the agency.

The story sounds like it’s all about this one heroic dude, but in actuality, this IAS officer could only take such actions because he had the full support of the state’s Chief Minister – the elected head of government, the big boss. I can’t believe my adviser takes so long to bring this point up, either. If a boss protects his workers’ efforts to do what’s right, then they’re more likely to make those decisions.

This is just speculation, but I also wonder if this contributes to IAS officers challenging people to take them to court. Of course, no one likes being sued, but maybe officers’ hands can be tied so badly that the only way to make him/her move is through a court directive. The court directive trumps whatever other forces the officer faces. To the opposing local fellows, the officer can now say, “You can’t hold me responsible for taking this decision. The court is making me do it.”

2. Amount of risk in the decision itself. For less risky, “easier” decisions, this means that there are no powerful stakeholders working against the officer, and the decision looks good (or, at least, not harmful) for the current political party.

Who’s really going to argue with tree planting and affordable housing projects on barren, government-owned land that’s super far outside of the city? I’m not trying to dis the guy who did these projects, but the decision to push them forward is not incredibly difficult if there are not powerful vested interests involved (and admittedly, I need to do more research to ensure that this isn’t the case – though I do think that the only people who got mad about the trees were those who disagreed about the variety that was planted; it was kind of a non-issue).

Hm, those are the main ideas in my head for now. My adviser told me that he’s been working on his notes from our meetings as well. I’m looking forward to hearing about what he’s been thinking about, since we tend to think somewhat differently. He seems to focus much more on the individual personality traits and backgrounds of effective/good IAS officers, and I want to figure out how regular IAS guys make choices. We’ll see how this works out.

The Grey Area: What Does it Mean to be “Corrupt”?

I spent the entire afternoon in a few coffee shops, typing up my notes from the past three meetings. The first was with the ex-IAS officer, the second was with a developer, and the third was with the principal of a secondary school (if that sounds unimpressive, let me just tell you that he wears many hats). Each person provided a very different perspective on the IAS and Indian bureaucracy. Each perspective was tainted by experience (working as an officer or working with officers) and personal background (religion, caste, etc). By the end of these interviews, my head was spinning, but I think I’m piecing together an interesting puzzle about bureaucrats here. There is a lot more for me to learn, and perhaps these “findings” are somewhat naïve, but I think I’m moving along.

I’ve been noticing that everyday folk – the public – have a really simplistic understanding of IAS officers. When I tell locals about my research topic, most reply, “All IAS officers are corrupt!” This is the image that the media – often paid for by the private sector – paint of IAS officers in “masala papers” (more or less every Indian paper except, perhaps, The Hindu). And, yes, there are officers who are definitely corrupt. Hopefully they end up in jail. On the other side of the spectrum, there are really great, selfless officers who do amazing work. You don’t hear about them much because there aren’t many of them, and the media doesn’t think that officers doing what they’re supposed to do makes for great stories.

In most cases, though, what is “corrupt” and what is “clean” is really blurry. I don’t think that most people really know what they mean when they use either term. The reality is that IAS officers are hard-pressed from all sides – their political bosses who basically determine where they’re posted in the state, senior bureaucrats, the courts/judiciary, the legislative committee, and the common people who can take up a case against IAS officers. One person I talked with said: “At the moment, an IAS officer has his hands tied behind his back, is bounded, and is told to run a marathon.”

Yes, IAS officers are supposed to do social good as administrators, but sometimes that social good is personal political/financial/lifestyle suicide. Like all thinking people, most IAS officers do not willingly throw themselves under buses. I don’t think they aspired to be martyrs for the social good. They watch their own backs, too, to make sure they please their bosses, provide for their families, and, when they retire, have a “clean” name and get some good postings.

As a result, many IAS officers are incredibly indecisive and suffer from “policy paralysis.” Even if they’re “supposed” to do something by law, there are local forces that may influence them more directly than the law. I’ve been hearing stories of IAS officers telling people to take them to court, and I wonder if that’s a way for them to do what they’re supposed to do. They just need that direct, personalized order to do it and to not succumb to whatever that local force is (but alas, this is just speculation).

Other IAS officers will take decisions, but along the way, they might take a bribe or two. I wouldn’t necessarily assume that they take bribes for mere personal gain, though. Rather, taking a bribe might be a way to mitigate personal risk – a security, in a way. The rationale is: Well, if this decision is going to hurt me, then at least I got a house out of it. This truly says something about the rewards for being a good, clean, hardworking, public servant of integrity. Right. There really don’t seem to be any of significance – no incentive to be “clean,” just punishment if you’re doing something that some watchdog is unhappy with.

I don’t condone “corruption,” but I’m still a bit confused about what corruption is. I’m not sure what kind of IAS officer is “better” or “worse” or “corrupt” or “clean” – the one who doesn’t take bribes but doesn’t do anything, or the one who takes bribes but does something (I also acknowledge that these categories are not clearly cut and that some take bribes but don’t do anything!). I’d like to say that making a decision is better than not making a decision, regardless of the route taken to get there, but I don’t want to go all Machiavellian either.

More puzzle pieces to come.

Meetings with the Big Guys

Whew, things have been getting busy out here in Bangalore. I haven’t been getting the time to sleep much, let alone write blog entries. But today I have a few hours in a remarkably tasty and tasteful coffee shop, and I feel more up to writing.

Monday was an eventful day. Steve has been really good about jam-packing my schedule (I’m not being sarcastic – I actually requested for him to do this for the sake of efficiency). We met up with five of Bangalore’s big guys in five hotels over five cups of coffee/tea. Needless to say, by the end of the day, my body was physically tired but my mind was quite buzzed on caffeine.

The purpose of these meetings was to introduce me, the Fulbright researcher, to the Centre for Contemporary Issues friends (research subjects?). Before launching into formal interviews, Steve felt that it was necessary for these guys to feel comfortable around me. We talked with a leader in education, a leader in water and sanitation, two real estate developers who has dealt with IAS officers, and an ex-IAS officer who quit just before retirement.

I won’t go into detail about what we talked about, since none of this was on the record, and a lot of it was small talk to make everyone comfortable. However, a lot of common themes did arise.

The first is that a lot of the knowledge and insights currently possessed by active and retired IAS officers gets lost. There is very little written tradition here. I think most of the men we talked with can speak an entire book verbatim, but they wouldn’t take the time to write it down. I suppose that’s where Steve and I come in.

The second is that India is filled with potential, but despite the potential, very little progress is being driven from within the nation. That is, money is being poured into higher education, but there are few tangible results. Why is this? The private sector guys – economic conservatives, definitely – have their own opinions here. Public sector guys would say otherwise.

The third is that systemic, institutional change within public organizations and an organization like the Indian Administrative Service is needed to sustain social good. Okay, this is a given. The more interesting question is how to implement such changes. What becomes the role and motivation of a public manager who 1) is a generalist, not a specialist, 2) frequently rotates postings, 3) can’t fire people, and 4) has so many incentives to not upset the status quo? How does a leader shape an organization so that it can run without him.

This morning, I was so pooped that I overslept by three hours and missed my meeting with a retired IAS officer. Fortunately, he was lenient with me; he’s retired, after all, and was hanging out at home. He also has daughters who are about my age and understands our limits. Steve and I met up with him later in the morning, and we talked about the entire system in which IAS officers operate. If we insist on looking at the big picture, though, then the primary question becomes: Where can we make the first change? On the theoretical level, that’s hard to figure out. But Steve has consciously decided to focus on IAS officers for the period of my Fulbright study. We’ll see what happens from there.

Interview #2 with Bharat Lal Meena and Bandhs

Sorry about the massive delay in updating. Things have been busy, and research is moving along.

Sorry about the massive delay in updating. Things have been busy, and research is moving along.

This photo was taken a few weeks ago at the Karnataka Secretariat in Bangalore. Steve and I were here to continue our interview with Bharat Lal Meena, who’s now in charge of the entire state’s agriculture. It was my first visit to the Secretariat, which Steve describes as “the halls of power.” They seemed a bit dusty to me. But of course, the interior of Bharat Lal Meena’s office was spotless. That distinction between what is “mine” and what is “everybody else’s (which really equals nobody’s)” is quite evident in all places around the city.

The interview was mostly about Pilikula Nisargadhama, a jungle resort outside of Mangalore in western Karnataka. Meena helped spearhead the project, and he was able to get local leaders to become involved and to take ownership of it for sustainability — a topic that has been coming up in my more recent discussions with other active IAS officers (gotta institutionalize that organizational change). I’ll be making a site visit to the resort at the end of this week with another Fulbrighter, and hopefully we’ll be able to see some tigers.

Since it’s been awhile since the interview, I can barely remember other topics that we talked about (it’s all on video and voice recorder, thankfully, but now I need to sit down and transcribe it). To me, the most memorable aspect of the discussion was that it took place during a bandh. And this was the first bandh I had ever experienced in India.

What is a bandh? It’s state-wide shut-down for political reasons. And I mean, literally, Bangalore is shut down — shops, restaurants, public transportation — that which create public life — are closed from 6am to 6pm for fear of being heckled by the political party that supported the bandh. This day’s bandh was a protest against national diesel price increases and the allowance of foreign direct investment in multi-brand retail. Just last week, there was another bandh protesting against sharing local water sources with another state. Although bandh days are free holidays, they’re such productivity killers.

Anyway, that Bharat Lal Meena wanted to talk during a bandh was quite telling of his own management style. He has the apolitical nature of the ideal IAS officer: able to remain effective even as political tides ebb and flow and able to work across political parties to get things done.

Interview #1: Bharat Lal Meena, IAS

This morning, we had our first interview with our first IAS officer, Bharat Lal Meena. Meena is currently the Principal Secretary for the State of Karnataka’s Department of Agriculture. Given that elections are fought and won (or lost) based on agricultural policy and action, Meena is in an important spot. The decisions he makes in this leadership position will affect literally millions of farmers.

This morning, we had our first interview with our first IAS officer, Bharat Lal Meena. Meena is currently the Principal Secretary for the State of Karnataka’s Department of Agriculture. Given that elections are fought and won (or lost) based on agricultural policy and action, Meena is in an important spot. The decisions he makes in this leadership position will affect literally millions of farmers.

I first met Bharat Lal Meena when he was the Commissioner for the Bangalore Development Authority, and there’s some type of drive in him that motivates him to keep going in the civil service despite the red tape and the pressures from above (political bosses) and below (angry citizens). Not that we want to distill principles down to the individual level — which is not a principle at all — but we do want to understand how folks like Meena have been shaped, encouraged, and motivated to act where other men (and few women) prefer to keep comfortable by doing nothing. Then we want to know just how he brings change to multiple stodgy, somewhat stifling organizations whose previous managers wanted to keep the status quo.

Today we talked about his childhood journey and his motivations to join and sustain a career in civil service. Unlike some of the other officers, Meena comes from a disadvantaged background and grew up in the poorer state of Rajasthan. A lot of these experiences push him to make the most of any position he’s in. And within these positions, he knows how to manage . Although he may not have the technical expertise for urban development or agriculture, he understands how to incentivize, encourage, or move people to get things done (his degree in political science, he says, helped him to understand power). This includes working with vested interests in the form of politicians and industry, community members (whom he helps organize behind the scenes so that they apply the right pressure on the local government; Meena excels at coalition building), and his own staff, whom he is usually not allowed to fire.

For better or for worse (well, likely the latter), politics and bureaucracy are inextricably intertwined. In this context, a successful manager knows when to press on and when to let go so that people benefit and so that he/she doesn’t get moved to a new position in the boonies. And that is a lot harder than it sounds.

Research Update: Less Urban Development, More Public Administration

It’s been awhile since I’ve written about the Fulbright research. Just to let you know, though — it’s actually going on! At least, Steve and I are brainstorming and planning. We met for a Chinese-Indian lunch buffet (at a restaurant named “3/4 Chinese,” although it’s probably more apt to call it “1/4 Chinese” — or maybe “1/8 Chinese”), where we were just not on the same page for awhile regarding the research. I had written my proposal around issues of land development, but our IAS officer who was leading the Bangalore Development Authority was promoted. It was still feasible to focus on inner-city development issues, but then the head of the Bangalore City Corporation (the BBMP) was also moved.

Oh, India and your “steel frame” of administrators — you’re supposed to be sturdy, but your pieces seem too replaceable.

With land and urban development out of the picture, the other feasible research topics, based on personal connections, were water and electricity. Unfortunately, I don’t know much about either, and nine months is far too short to learn an entirely new subject. Nor did I want to be extremely technical in this research project; I’m not here to write out a master plan for the city or make purely technical recommendations. That’s what hired contractors do, and it’s not like anyone actually follows the plan anyway.

And thus, my research topic took a turn for, what Steve and I believe, is the better (and yes, we’re now on the same page). The focus is now more about public administration — or rather, public administrators themselves. How do people like these bring positive change, even though they’re so constrained by the system? It may seem difficult, but it’s not impossible. In the state of Karnataka, there are a few examples of public administrators who have actually done good things (not everyone is corrupt!). It’s now my goal to learn lessons from these short-listed fellows (unfortunately, just fellows — we haven’t yet been able to identify any ladies!). Lots of writings and a conference are planned. Let’s do it!

And thus, my research topic took a turn for, what Steve and I believe, is the better (and yes, we’re now on the same page). The focus is now more about public administration — or rather, public administrators themselves. How do people like these bring positive change, even though they’re so constrained by the system? It may seem difficult, but it’s not impossible. In the state of Karnataka, there are a few examples of public administrators who have actually done good things (not everyone is corrupt!). It’s now my goal to learn lessons from these short-listed fellows (unfortunately, just fellows — we haven’t yet been able to identify any ladies!). Lots of writings and a conference are planned. Let’s do it!

leave a comment